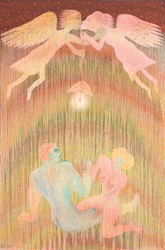

Kaletski is first a painter but he was and remains a well-known actor in Russia. He just completed a self-produced film in the USA (Song of Silence) with his wife. He is a musician and he has written several novels, including a best-seller.

At Art Miami, during Art Basel in Miami, some of Kaletski’s work on cardboard was on display. What drove him, after emigrating, to work in this peculiar medium? The motive wasn’t totally aesthetic.

“I always wanted to paint oil on canvas, when I came to America I had no money. I couldn’t.” he says.

But wandering around in New York, he saw something beautiful—and something scarce in Russia, or at least not piled up on the street.

“I saw, on the streets of New York, there was recycling, pieces of cardboard. Coming from Russia they looked so beautiful. There was no cardboard in Russia. Each box was a masterpiece in my eyes.” says Kaletski.

And Kaletski made many pieces from cardboard and continued to work with what we throw away, even after his finances improved and he could afford canvas. There is something in this about America and Americans—something sort of sad. What we throw away others can find beautiful and make more beautiful. We take our beautiful junk for granted.

Kaletski didn’t, and doesn’t. He still makes his cardboard paintings. And it isn't just slapping paint on cardboard. He first applied white or black gesso (used to prepare canvas as well).

“You can put oil on cardboard but it eats cardboard and makes ugly spots. Sometimes I use pastel and you can mix that with gesso. When gesso is on cardboard you can put oil on top of it—whatever comes to mind and is nearby, glue…When I start with cardboard I never know what I am going to do. The spirit of the cardboard comes out of the box.” says Kaletski.

“All painting I tried to do is experimental, every show is different. I try to do something different technically.” he says.

He considers the oil work to be his experimental, serious work. While his oils are drying he works on cardboard pieces which he says are for “fun and the soul.”

Creating is what fuels Kaletski’s soul and even in a brief conversation you come to understand the challenges faced by a creative mind in the repressive system that was the USSR.

“When I was a child I was painting all the time—I won every children’s competition. When I was older I had to go to University,’ says Kaletski. “In Russia at that time you picked an area of training and that is what you did for the rest of your life.”

And if you decided to be a painter you didn’t run with your muse. You didn’t try to create something new; after all, you lived in a society that was already the perfect ideal.

“You had to paint Socialist Realism. You couldn’t paint anything except this style. They had even started to teach the style in the children’s classes.” he says.

He didn’t want to do it. More than that, given his temperament, his spirit, he couldn’t do it.

“I didn’t want to follow instructions” he says—a trait unlikely to lead to success in the USSR.

He also realized that the training would kill his love of painting. So Kaletski took a different tack. He opted instead to go to theater school—an exclusive one—and studied to be an actor. He could act and he could do it within the confines of the system because, while it is something he enjoys and excels at, it wasn’t part of his soul like painting.

“I became a successful actor involved in those stupid Soviet movies. I hated them.” he says

But they gave him money to live on and he kept painting and writing songs on his own. While making the films and being an actor he also lived a double life.

“I still painted and made collages of Soviet posters. They are always the same colors. I sold the drawings to foreigners. It was considered to be a crime. I was also writing songs. I would say songs of protest but very independent. It was about the same time, in America, as Bob Dylan,” he says. “It was parallel. Songs and paintings were underground. I got really involved in the underground—living in Moscow illegally.”

Being involved in the underground, selling paintings, writing protest songs was a dangerous thing to do. American singers of such music often feel put upon. In some cases they have been harassed but the situation in the Soviet Union it was far worse. Kaletski feared he might be caught with his art or music and sent to a psychiatric hospital. If you were against the perfect Soviet system? You were obviously insane.

He decided to leave the USSR.

“In America I first made living selling paintings, performing at colleges or at Russian Clubs. I sang in Russia. It was natural for me to do different things.” he says.

He also made money hand painting silks for boutiques. This is not so far, perhaps, from painting on linen in form. It clearly had to differ in style (alas fashion is not always art).

One of a series of five short films by Kaletski and Anna Zorina

“I was anti-communist and want to help America fight communism. It sounds idiotic now.” he says.

But it was his mission, fighting communism. He wanted to show people that the glimpses of freedom Russians had. He brought the underground to America. Yet it his ideal of America and the reality did not mesh. It was culturally horrible for him. He liked the country and the political system but day to day living was not what he had pictured. It took time but eventually he came to terms with his new home.

“I got past ideology and how America can be a tough place. I thought America would take me as a hero fighting communism but no one gave a shit.” he says, laughing. “Now I know what America is and I love America. Nothing is easy her but you can do whatever you want. Still, in my heart, I am a Russian idealist.”

Imagine being a movie star, an idealist, an anti-communist, who moves to the leading nation in the west and no one cares. Imagine you wind up painting on cardboard because you have no money. But also imagine being able to find beauty and wonder in the cardboard. It worked out. The cardboard paintings helped keep his soul intact.

They cost him little but no one wanted to buy them (at the time). He did it for himself, to satisfy his need to create. It is a lesson to artists. The best work isn’t what you create to hang in a bank lobby or a commissioned painting of a rich old lady’s poodle. It is what you create for no reason other than you feel compelled to make it.

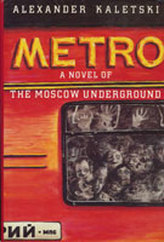

Kaletski became something of a celebrity. He was on the Merv Griffin Show twice—once with Arnold Schwarzenegger. His wonderful quasi-autobiographical book, Metro, became a best seller. Griffin was taken with Kaletski and his story and therein is the origin of Metro.

“Once I was on his show as a singer. He said; ‘You have such a great story, let’s make a movie'.” says Kaletski.

They gave him a writer. Kaletski didn’t like what he was writing and asked for a new writer, He was told “no” and decided to write it himself. It took seven years. Metro became a best seller but the film was never made.

“Then I write to punish myself. Writing is the most difficult thing for me.” he says.

He writes for 40 minutes to an hour. He has written another three novels but painting has remained most important to him. It has not kept him from branching out further.

“I just finished a movie, acting as myself. There is my music, my story. My wife and I are finishing it in two or three weeks. It is fiction, a murder mystery.” he says.

Song of Silence premiered in New York City In February 2012.

He also still acts in Russian movies.

His main work, however, remains painting. It isn’t just work though. Painting is a spiritual activity. When he discusses his work, his process, you get the feeling you are talking to a mystic about some secret rite. But then his ease and good humor transform that spell.

Despite the effort he puts into it. Despite the hardships he endured to become an artist, Kaletski has, perhaps, a surprising view on what makes good painting.

“Good painting should be random. It should be accidental.” he says.

Art should be, perhaps, as accidental as finding beautiful bits of cardboard that others, unseeing, throw away.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed