by Patrick Ogle

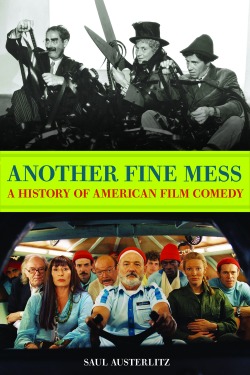

Saul Austerlitz, a writer and critic living in New York, will shortly release Another Fine Mess A History of American Film Comedy and explore the history and the now of the American comedy. The fact that comedies are given short shrift at award time was part of the impetus to write this book.

“The types of movies that win Oscars are serious. I have nothing against those movies but think it is interesting how some performers are deemed ‘ineligible’ to win these awards,” he says. “Comedians understand how the game is played. Look at Jim Carey twisting himself into a pretzel to play dramatic roles.”

Austerlitz allows that Carey did a fine job in some of his more serious roles but adds; “It isn’t really his forte.”

Think of all the comedic talents, directors, actors and those who wore both hats that never won an Oscar. Charles Chaplin never won an Oscar. Honorary or “special” Oscars don’t count, those are usually, Oops-you-are-really-great-and-might-die-soon.” awards. The dearth of major awards for comedies is easy to trace. Go to the Academy Website. Less so are the roots of American Comedy.

“The thing people might find surprising is the interconnection of people within the book. It was more than an abstract idea but a sort of guild. One comedian passed on to another, stocked one another.” says Austerlitz.

Comedians also change and adapt over their careers.

“Jerry Lewis in the 50s began as an incredibly low-brow, eternal child to go solo and try to take on high comedy,” says Austerlitz. “I would probably argue that in his middle period work he was still playing, for lack of a better word, a ‘dipshit’ but he is taking on multiple roles, director, actor and more.”

Austerlitz says this is a reflection of the Chaplin influence. But how many of Lewis’ films really stand the test of time?

“There are probably two of them worth checking out again before he goes about being famous in France and telethons. His most successful film is Nutty Professor,” says Austerlitz. “His plays a second role, understood to be Dean Martin but a better way to reflect on the film is as two sides of Jerry Lewis. It has a lot of fun balancing those two roles.”

And it doesn’t suck like the Eddie Murphy remake either.

Another film Austerlitz recommends from Lewis is The Bell Boy.

“The Bell Boy is a much more low-key film. It is less hectic and loud. It is almost silent. His character has one line.” says Austerlitz. “The film is an attempt to bring back or update the silent film”

The film also has a dead ringer for Stan Laurel says Austerlitz and it is hard to imagine that is an accident.

“My Favorite Brunette is actually a pretty good film. Hope was a self-deprecating one-liner machine.” says Austerlitz.

Today’s audiences can decide for themselves how well the humor stands up. One comedian/filmmaker who is universally thought to stand up is, obviously Charles Chaplin but he is more than just an actor or director. It is pretty unfair to compare other comedians to Chaplin and not just because of his control over his projects. Indeed, Austerlitz believes that an actor can influence a comedic film more than dramas.

“I don’t think anyone can be compared to Chaplin in his effect on film history and culture—or on American culture, period, with a very few exceptions. But I think that, on the whole, an actor can, and have, had an enormous impact on the growth and development of comedy,” says Austerlitz. “Comedy is a performer’s medium, to a large extent, and a talented actor like (Bill) Murray can place his imprint on a film as much as, if not more than, their directors. Rushmore and Groundhog Day and Lost in Translation are Bill Murray movies as much as they are films by Wes Anderson, Harold Ramis and Sofia Coppola. There is a notable difference in the variety of the talents displayed by an actor-director like, say, Jerry Lewis, as compared to an actor like Peter Sellers, but I wouldn’t necessarily rank Lewis ahead of Sellers merely because he directed as well as acted.”

Another example of a performer, “just an actor,” having a profound impact on films is the regrettably overlooked, Harold Lloyd.

“Chaplin is the ideal of people who did everything. Keaton did some of his own directing but advisors. Lloyd didn’t direct his own films but he put his own stamp on them. Lloyd, even though the least remembered, may have been the most successful. He had a studio, set of directors and gag men.” says Austerlitz.

Lloyd was a producer and more and while he may have started out as a sort of Chaplin-esque character, he evolved.

One of these is Doris Day.

“She has become a punch line in movies about chastity. The movies she did with Rock Hudson were better than we remember. We think of them as Doris Day being chased around the room by some horny guy. They are quite modern for the times about young single, upwardly mobile people,” he says. “Doris Day is just as much an icon of 50s female sensibility as Marilyn Monroe. The time is ideal for Day to be recovered as a performer and not a ridiculous parody of herself.”

And where are the current non-painful romantic comedies? The ones with no J-Lo?

“I think it is, in part, that there are not a lot of performers whose performances translate to that genre and the most talented directors are not making those movies. It seems like a genre that, for the moment, has run its course.” says Austerlitz.

The world really needs Christian Bale in a remake of Pillow Talk.

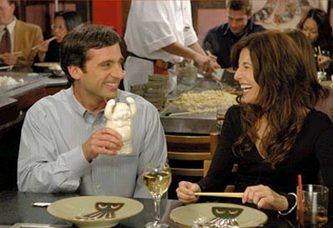

Though the romantic comedy may be in the creative doldrums, Austerlitz contends that another sub-genre is not: the trash guy comedy. Austerlitz credits Judd Apatow with rescuing this genre from simply being eternal remakes of Porky’s and Hollywood Knights.

“I think Judd Apatow is unique in the way he has skillfully integrated raunchy guy comedy with a subtle emotional palette heretofore unknown to the genre. The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up in particular, are hilarious, unadulterated comedies of masculine aimlessness that manage to capture something very real—about relationships, about contemporary life, and most of all, about the ways men relate to each other,” he says. “Apatow is a poet of masculinity, and his films demonstrate a remarkable understanding of, and sympathy for, his male characters. That said all of that would be enough, together with four dollars, to purchase a tall latte at Starbucks if he weren’t also blessed with the gift of writing exceptionally funny dialogue. Knocked Up, in particular, is a gold mine of brilliant comic roughhousing.”

And yet, getting back into the dearth of awards train of thought, how often have you heard Apatow’s name called on Oscar night? There should be a new high end award, perhaps “The Chaplin” (please don’t sue me Chaplin family) for comedies. They can give whoever directed Porky’s an honorary one to start things off right.

Beyond Apatow, Austerlitz singles out another group of contemporary comedians for special attention: Will Ferrell and Ben Stiller.

“Ferrell is a personal favorite of mine. He is, I suppose, a one-joke comedian—the cloddish boor triumphant—but hell if it isn’t a surprisingly flexible joke. And didn’t W.C. Fields make his own version of that same joke last for an entire career, too?” says Austerlitz.

Stiller’s work is a different sort of creature to Austerlitz.

“It’s more inward-looking, more directed at skewering himself and his own delusions of grandeur. If you look at the films Stiller has made like Reality Bites or Dodgeball or Tropic Thunder, he is often the butt of his own jokes,” he says. “Stiller refuses to wink at the audience—to acknowledge in any way that his portraits of odious strivers and petty tyrants are in any way meant satirically, or that the real Ben Stiller is somehow superior to the characters he plays—and that, ultimately, is his saving grace.”

Austerlitz notes a somber note in the book, one Chaplin’s protagonist in Limelight articulates.

“The slightly depressing undercurrent of my book is that nearly every major comedic talent eventually does stumble. Comedy is a fickle master, and even the greatest comedians eventually lose whatever mysterious spark it was that allowed them to succeed,” says Austerlitz. “Often, their time at the top of the comedic heap is surprisingly short—look at someone like Preston Sturges, whose brilliant run of films lasted approximately 5 years, or Buster Keaton. Being funny, it seems, is not like being a skilled actor or a superb writer. It is a skill that emerges mysteriously and disappears with just as little warning. Comedians’ lives are often depressing to exactly the extent that they fail to understand the fragility of their gifts.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed