photo by Justin Patrick

photo by Justin Patrick Porky Hefer is a South African artist, designer and activist. His designs are not just about a neat looking sofa; there is a deeper current to the work, a re-connection with the natural world. One of the myriad starting points for Hefer's work is the weaver bird. These birds weave nests out of bits of vegetation and other materials.

"The Weaverbirds or Ploceidae feature mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa and build roofed nests that vary in form and material. Their name is a testament to their prowess. Every home I have lived in has had either one or two pairs or a colony in it. Their building style is captivating and masterful and the ensuing courtship procedure captured my attention from a very early stage," says Hefer. "My father was a keen birder and we spent many hours of my youth following and studying South Africa’s amazing bird life. We did regular ritual visits to game farms and the avians were given as much importance as the big five in my father’s car."

Hefer says that he liked the idea of suspending shelter rather than erecting it, trying to find the lightest footprint possible.

"Why not use an existing footprint?' he says.

Beyond this utilitarian reason Hefer was drawn to this architecture of birds and its broader implication.

"Birds and their architecture started me thinking about seasonal, sustainable architecture that were simple functional forms. The Ploceidae also make the most variations of nest shape than any other family of birds," he says. "The are spread out over more varied climates and vegetations and have managed to adapt their nests and technique to survive."

In other words there is a lot we can learn from these birds. Ultimately his path to the weaverbird's creation was a result of his personal philosophy.

"I follow Buckminster Fuller's philosophy of trying to predict trends rather than following current ones. Find most of my inspiration from nature and looking a little closer at everyday life and the things in our immediate environment that we often take for granted," says Hefer. "I am a big believer in, follower and fan of vernacular architecture. We have been building like that for thousands of years why change. Animals are vernacular architects and we can learn a lot

from them about materials and form."

He began looking at indigenous, aboriginal, ancestral and traditional architecture. These forms of architecture are, unsurprisingly, created using local material and local tradition.

"Although this is against the trend of modernization and globalization it makes absolute sense in this day and age." he says.

"The use of local techniques helps preserve local traditions.I believe this is a very necessary task as I see tradition disappearing fast as the globalization of identity, quality and success ensure new generations drop the traditions of the past and embrace a far more homogenized future," says Hefer. "I really love it when I go to a place and it has a definite sense of place. I believe you should know where you are. Language and culture play a big part in this but architecture has a very important silent role in creating place. I believe geography and culture will become the new religion. It's all we have as differentiators now that the world has become so same same."

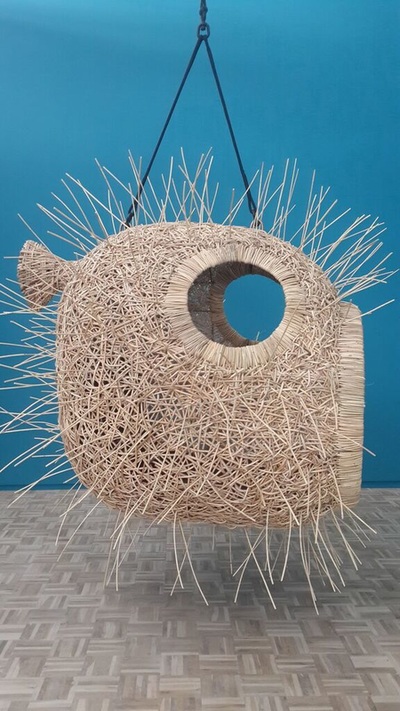

The work shown here (you can see more work by going HERE or to the Southern Guild website) are riffs on the theme already mentioned; the nests of the weaverbird. As you will note there has been a progression from the actual nests to more whimsical pieces depicting a variety of animals.

"The underwater theme was an extension of suspension. you are suspended in water, for me the roof became the water surface. It’s harder to suspend outdoors as you need a tree or hook of some sort," says Hefer. "If your roof is strong enough you can hang anything. So my mind wandered. It all started with the angler fish. It was more the light that attracted me in the first place and the first three were more focused on this theme."

These pieces have names and personalities. There is Grace the Hippo, Fiona Blackfish the Killer Whale, Eugenie the croc. Some of these have plush teeth and others harder, sharper teeth.

“... the pelican is a great bit of design.His beak/throat is a ... net for fishing. Its also very comical.The shape and space of the gallery also dictated the theme. It became the perfect fish tank,” he says. “Not often do you have the ability to play with the top plane of a space as they are usually so low and restricting."

photos by Justin Patrick

"The pie chart tables were just an exploration to see if I could do furniture as 3 dimensional informatics. The bigger idea was public seating at the Cape Town station which were also infomatics about how people traveled around Cape Town," he says. "The right angles actually all come together to form a circle so we are back to flow."

Hefer's work, as you may have noticed, is about more than just the pieces. There is a broad philosophy here, a wariness of technology (although shy of techno-phobia). There is a concern about the loss of tradition, of the differences in people and culture that make the world so fascinating. Hefer's work brings you back to nature, closer to the outdoors, and therefore, our roots.

"I think my nests put you in nature and you become part of nature as opposed to most buildings which tend to separate or protect you from nature. This gives humans a superiority complex and they feel omnipotent.” he says.

All of these pieces are low tech. Hefer says they are almost analog with a computer used only for the logo. They are almost alive to Hefer.

“They are tactile and real and almost primal, they even smell. The handcraft and individualness comes through and you start treating them like they are alive, they even have names like Joyce, Grace and Dora. I worry about technology taking people further and further away from reality, literally." he says.

Hefer works with local craftsmen in various techniques and believes it is important to protect and preserve their traditions.

"It's what makes us unique from the rest of the world. But I suppose it is this that the modern youth are rejecting on their way to a more global existence. We know use Korean technology to do African business," he says. "Strange. It's in our DNA. It can mobilize a workforce. It can transform a community. It can create economy, it is sustainable due to the fact that it uses local materials and skills. Its really a no-brainer."

It is possible to quibble with the notion that "modern youth" are the problem. The youth hardly created the technology and if traditions are to be preserved they will be the people who do it. Yet, the turning away from what when before is undeniable. People can turn back to their roots, however, and many do.

Hefer is also concerned about how technology is causing the "expert' to vanish--or, perhaps more accurately how the notion of what is an expert has changed.

"The expert nowadays is not the person with the most experience and knowledge of a particular field or subject but rather the developer of the idea as they are the only one that know how it operates," he says. "This downgrading of knowledge and experience are seriously worrying as its starts to strip away the traditions and cultures of our world. I believe that the revitalization of crafts has highlighted the importance of the guru on the mountain."

One final part--and an interesting part--of Hefer's work is how he works to keep his creations locally based--both with regard to materials and expertise.

"The way I work is find an interesting technique or craftsman and then design around their strengths. I find we tend to have an idea then contact a craftsman and ask him to do something he doesn’t normally do. This leaves you with an insecure craftsman and disillusioned designer and a crap product."

And these products are not crap and they are more than just products; they are an attempt to give traditions that are disappearing relevance in the modern, technological world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed